Nagorno-Karabakh Dissolution

A heavily quoted guide to what is going on in a region not many people are paying attention to

After the fall of the Soviet Union, the region between Armenia and Azerbaijan was hotly contested and had led to two wars. But on Friday, the self-declared Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh announced its dissolution and will not be a state in 2024. The lead-up contained a blitz Azerbaijan strike and Armenian refugees fleeing in droves. As the BBC reports:

The leader of the self-declared Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh has said it will cease to exist in the new year.

Samvel Shahramanyan announced on Thursday that he had signed an order dissolving all state institutions from 1 January.

The region, which had been controlled by Armenians for three decades, was seized by Azerbaijan last week.

More than half of its majority ethnic Armenian population have now fled, according to officials.

The region is recognised internationally as part of Azerbaijan but Armenia took control in the 1990s following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

It re-orients the geo-political stage for the region, as the New York Times wrote:

The return of the enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh to Azerbaijani control is also likely to alter power dynamics in the South Caucasus, a region that for centuries has been at the crossroad of geopolitical interests of Russia, Turkey and Western nations.

Decades of violence and geopolitical rivalry underpin the dispute between the two former Soviet republics over the enclave, which lies within Azerbaijan’s internationally recognized borders and has been home to tens of thousands of ethnic Armenians.

Armenian separatists’ surrender could hasten the decline of Russian influence in the Caucasus, where Moscow’s role as an arbiter in the conflict made it a pivotal power. It could also threaten instability in Armenia, where Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan has sought to build closer ties with the West despite a military alliance with Russia.

If anyone is up for a history lesson, here is the context provided by Reuters on the region and its past:

Nagorno-Karabakh, known as Artsakh by Armenians, is a mountainous region at the southern end of the Karabakh mountain range, within Azerbaijan. It is internationally recognised as part of Azerbaijan, but its 120,000 inhabitants are predominantly ethnic Armenians. They have their own government which is close to Armenia but not officially recognised by Armenia or any other country.

Armenians, who are Christian, claim a long presence in the area, dating back to several centuries before Christ. Azerbaijan, whose inhabitants are mostly Turkic Muslims, also claims deep historical ties to the region, which over the centuries has come under the sway of Persians, Turks and Russians. Bloody conflict between the two peoples goes back more than a century.

Under the Soviet Union, Nagorno-Karabakh became an autonomous region within the republic of Azerbaijan.

As the Soviet Union crumbled, the First Karabakh War (1988-1994) erupted between Armenians and their Azeri neighbours. About 30,000 people were killed and more than a million displaced. Most of those were Azeris driven from their homes when the Armenian side ended up in control of Nagorno-Karabakh itself and swathes of seven surrounding districts.

In 2020, after decades of intermittent skirmishes, Azerbaijan began a military operation that became the Second Karabakh War, swiftly breaking through Armenian defences. It won a resounding victory in 44 days, taking back the seven districts and about a third of Nagorno-Karabakh itself.

The use of drones bought from Turkey and Israel was cited by military analysts as one of the main reasons for Azerbaijan's victory. At least 6,500 people were killed.

Russia, which has a defence treaty with Armenia but also has good relations with Azerbaijan, negotiated a ceasefire.

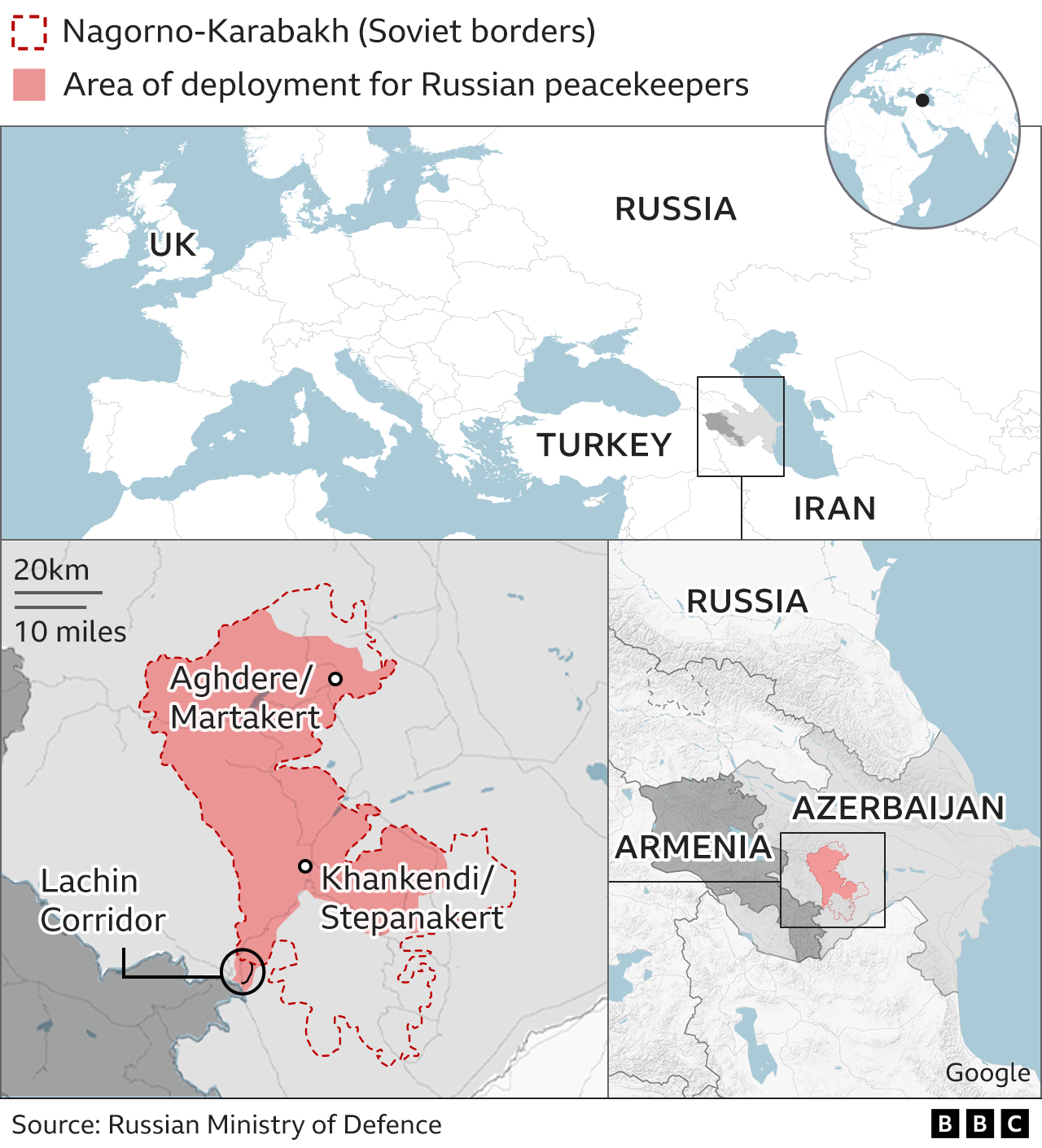

The deal provided for 1,960 Russian peacekeepers to guard the territory's lifeline to Armenia: the road through the "Lachin corridor", which Armenian forces no longer controlled.

After the 2020 war, peace talks were set up and mediated by the EU, the US, and Russia. A final settlement was not set even after pulling the two sides closer together to a permanent peace deal. In late 2022, violence rose after Azerbaijan achieved a blockade of a vital route into the Nagorno-Karabakh enclave. The Lachin Corridor was the only connection between the region and Armenia, and it was blocked by the Azerbaijani side who accused the other side of delivering weapons, a claim Armenia denies. As Armenia accused Russia of being distracted by the war in Ukraine, both the Armenian and Azerbaijani sides accused each other of building troops. Then in September, the Azerbaijians strike. Which hence leads to a humanitarian crisis, as The Economist notes:

Overwhelmed by Azerbaijan’s modern army, exhausted and starved by a nine-month blockade, isolated from its Armenian motherland and betrayed by Russia, which took it upon itself to provide security in the region, Nagorno-Karabakh had no option but to capitulate. As The Economist went to press, around 65,000 of the enclave’s ethnic Armenians (from a pre-war population of perhaps 120,000) had fled. Azerbaijan’s choice to attack the region rather than pursue a Western-backed deal guaranteeing the civil rights of its Armenian minority means that it is guilty of ethnic cleansing.

Beyond the two countries, the nations most affected are Russia and Turkey. Turkey, after emerging from the 2020 war as a key power broker, is reaping the wins from Azerbaijan, and is now considering making nice with Armenia after their loss. While for Russia, as the Washington Post reported on Russia’s abandoned commitments to Armenia, an ally:

The lightning military operation by Azerbaijan to seize back the disputed mountainous region made a mockery of President Vladimir Putin’s 2020 guarantee that Russian peacekeepers would protect the region’s population, maintain a cease-fire, and assure access on the only road connecting Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia, through the Lachin Corridor.

Russia failed on all three counts.

…

Putin’s spokesman Dmitry Peskov has insisted that Russia does not bear blame, and said that there was “no direct reason,” for the exodus, merely that “people are willing to leave.” His statement ignored repeated cycles of war and ethnic violence in the region.

“It is hardly possible to talk about who is to blame,” Peskov insisted Thursday amid mounting criticism of Russia. He described Baku’s swift moves to reimpose control over Nagorno-Karabakh, internationally-recognized as Azerbaijan’s sovereign territory, as “a new system of coordinates.” He said residents should get to know the agreements on living under Azerbaijani rule.

Many analysts ascribe the Russian failure down to the Kremlin being highly distracted by its war in Ukraine. The focus on the war has undermined Russia’s authority and influence throughout its geopolitical neighborhood, including the Caucasus and Central Asia.

It shows as the war in Ukraine absorbs the most attention from Putin, there are other things he should be worrying about. In the meantime, the world has to deal with a humanitarian crisis on its hands again, and this time there is no way of telling if will there be any support.